Language, translation, and the world of One Piece

I’ve been expecting this moment ever since the pandemic began. While I’ve been trying to focus on working through a backlog of new media or revisiting smaller series, the entire time I’ve been home the 73 volumes of One Piece sitting atop the headboard of my bed have been taunting me. It was only a matter of time before I finally committed myself to giving my favorite manga a reread.

One Piece occupies an interesting position in my life. I started following it in high school and, though the intensity of my devotion has waxed and waned, it’s been a consistent interest of mine ever since, simply because the series is still ongoing. Still, oftentimes I miss the intensity of my initial passion for it, when I had a whole new world to explore and hundreds and hundreds of chapters or episodes to catch up on. Reading one new chapter a week is an entirely different experience.

That idea of exploration is the key to understanding One Piece. The series is a shonen manga* about the age of pirates in a world of endless ocean. Monkey D. Luffy is a 17-year-old boy who wants to become the King of the Pirates, and fights for this goal using the power of a cursed fruit that turned his body into rubber.

It’s a deeply, deeply silly series that also tackles serious subjects like slavery and systematic oppression — not always with the deftest of touches, but in ways other series in the genre wouldn’t dare touch. As Luffy and his crew travel the world, each storyline takes them to new locations, allowing for shakeups in the tone and backgrounds that keep the story feeling fresh. Every new wonder Luffy’s crew discovers is a new wonder for the reader to discover too, and some of my favorite moments are when the story is briefly put on the back-burner in order to just immerse the cast and reader in a new location and civilization. It’s also made me cry more times than I can count. One Piece is essentially engineered to make the reader sob like an infant, not just over heroic sacrifices or the main cast’s tragic backstories, but even over the fate of a small dog, or a wild snake, or the “death” of a boat. Seriously, I’ve shed more tears over that stupid boat than I care to admit. For all his flaws (and it’s not a perfect series by any means), One Piece cartoonist Eiichiro Oda is a master storyteller (nobody can set up plot points and twists then pay them off hundreds of chapters later the way Oda can), and revisiting the series from the very beginning has been an absolute joy.

*Manga is just Japanese comics, and shonen is an action-focused genre aimed mostly at younger boys, around the age of 12 or so. Dragonball would be the most well-known example. That said, most shonen series have much wider audiences, and One Piece especially has a huge female fanbase, millions of adult fans, and from the very start was strangely popular with older women. It’s the best-selling manga in the world, and in everywhere but America is pretty much just widely and universally loved.

Interestingly, what really struck me during this reread was the particular translation I was reading. Obviously, unless you know Japanese, it’s impossible for an American to read and understand One Piece in its original form (though I do own an original Japanese volume of the manga just for kicks), and the translation you choose plays a huge role in how you experience and understand the series.

I was first introduced to One Piece by my best high school friend, who lent me the first 100 episodes or so of the anime adaptation on DVD (he had borrowed them from a kid who fell into a coma immediately afterwards, so I guess there was no rush to return them). There was no official American/English translations or releases at the time, meaning that everything was handled by fans, and the quality of translation — not to mention the editing — fluctuated wildly between each group of translators. Kaizoku Fansubs was the best and most well-known, translating accurately with great grammar and cute, color-coded subtitles. On the other end of the spectrum were some of the subs I received, which apparently had been translated from Japanese to Chinese, then Chinese to English. Yes, they were as bad as they sound.

Those translations were like reading the final result of a game of telephone. They couldn’t even get character names correct: Zoro became Sulon, Usopp became Lysop, and Luffy was Roof (there’s at least an explanation for that one: the letters L and R are interchangeable in Japanese, so Luffy got misinterpreted as Ruffy, and somehow that slowly morphed into Roof). The grammar was atrocious, to the point where there were entire scenes that I just couldn’t understand because the dialogue was incomprehensible to me. For example: in one sequence, swordsman Zoro defeats a villain named Hachi, who a few episodes later, in the middle of a different fight, stands back up and tries to attack Luffy only to have his wounds burst open and drop to the ground, down for good. The fan translation I had for that episode made it sound like Zoro used some kind of delayed reaction technique on him; it wasn’t until years later, after the official American release, when I realized that Hachi’s wounds just reopened because he tried to move too soon (in contrast to Zoro, who defeated him in combat despite still recovering from wounds several magnitudes beyond those he inflicted on Hachi himself).

At least their subtitles looked nice. When I ran out of DVDs I started downloading fan-translated chapters of the One Piece manga from the internet*, and man, scantilations are of even more dubious quality than subbed anime. Not only do you have the quality of the actual translations to worry about, but also the quality of the image. Scantilating involves scanning the original Japanese versions into a computer, removing Japanese text, and replacing it with the English translations (this was before the time of official online releases of the manga, which has increased the image quality and consistency in fan subs tremendously). Even good translations can be ruined by images that have become grainy after being scanned and saved multiple times or editors who use terrible fonts or don’t know how to properly fit text into word balloons. Lettering is an art too!

*At the time I had dial-up internet at home. It took me an hour to download a 19 page manga chapter, but at least that was manageable; while the episodes were available to download, it would have taken days for a single one, and I couldn’t tie up the phone line that long. I do not miss dial-up. In my senior year of high school I ended up downloading over 100 chapters to read on the school server, getting called down to the school office, and single-handidly getting the entire school internet heavily censored and restricted for the rest of the year. This is my legacy.

But even if you have the best translator in the world, problems still arise. Some aspects of Japanese culture in the story aren’t easily explained. Also, Oda is a writer who loves puns and likes to mix strange references and other foreign languages into his work (Sanji’s attack names are in French, for example). Even the structure of the Japanese language itself can prove to be a major challenge to translate, with words that can mean one thing when written but another thing when spoken. One of Zoro’s attack names has three or four concurrent meanings, and there’s no single English term that can encompass them all. It’s so complicated that I’m just going to post the One Piece wiki’s explanation (only the second half of this really matters):

The most infamous cultural difference, though, probably comes in the form of Luffy’s brother, Ace. On Ace’s back is a tattoo of a symbol called the “manji.” The manji is an ancient symbol that represents divinity and spirituality in certain Hindu and Buddhist religions. Unfortunately, the manji also looks quite a bit like a swastika.

While the American editor’s notes play the two symbols off as being completely unrelated, a quick Wikipedia search shows that the swastika used by Nazi Germany was their take on the manji (the symbol had represented good luck in the West up to that point). The manji is still well known in its original meaning in Japan and surrounding areas, meaning that Japanese audiences didn’t bat an eyelash at this, but outside of the East it obviously caused countless problems. Foreign translations had to cram massive editor’s notes into the margins of the pages explaining that, no, this isn’t a swastika. It was such a nightmare that in Ace’s next appearance his tattoo was changed entirely.

As far as I know, this is the only instance where issues with the series being released in other countries have led to changes in the original Japanese source material. It was the right move to make.

Some translation issues have led to infamous debates and wars among fans. The most famous of these involves the Japanese word “nakama.” The word essentially means “friend,” but has a stronger connotation of a found family, or friends with unshakable bonds, friends you’d die for. Finding and protecting your nakama is possibly the most important theme of One Piece, and thus the word evolved into a term early English-speaking fans used to describe the main characters as a group, similar to how, say, the cast of Dragonball Z were referred to as “Z Warriors” or the cast of Buffy the Vampire Slayer as “The Scooby Gang.” Kaizoku Fansubs popularized the habit by refusing to translate the word in their subtitles, a move that many loved at the time but is now mostly looked back on in hindsight with much cringing and some eye-rolling.

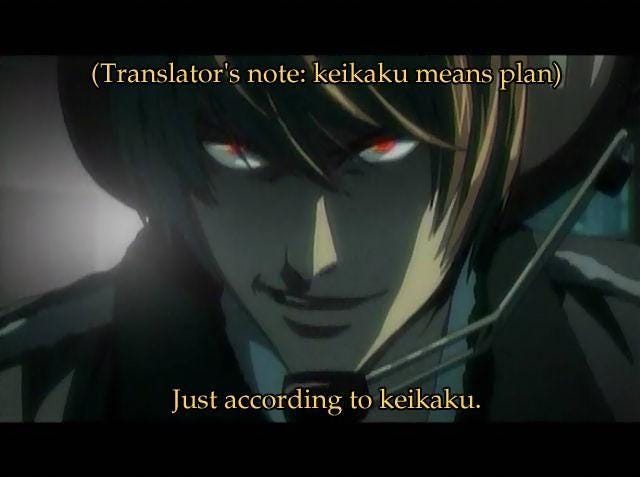

(It’s not quite as bad as this, but same energy for sure)

One of One Piece’s most famous and moving scenes involves Luffy standing atop the battered remains of Arlong Park, where he has just beaten the tar out of the man who enslaved Nami her entire life, and declaring “You are my nakama!” to tell her that she has a new family who loves her and will always care for her. It’s this scene that led to Kaizoku elevating the word nakama to a kind of mythical status, and it’s this scene that early fans feared the most when Viz’s official English translation got around to this point of the series. Viz sometimes translated “nakama” as friend, but the word doesn’t really have a strong enough connotation for this scene; they more often translated it as “shipmate,” which sounds too clinical for this scene. Ultimately, Viz went with “You’re one of us now!” which, surprisingly, seemed to satisfy pretty much everybody.

Most of these translation debates weren’t solved as easily or quickly. Early in the series it’s mentioned that the treasure known as the One Piece — which, when found, will make the owner the King of the Pirates — is hidden on an island called Raftel. It took almost 800 chapters for Oda to eventually spell the name of the island out in English in the manga, and it turns out it’s actually called “Laugh Tale!” It makes sense, as we’ve later learned that the legend of the One Piece involves an ancient figure known as Joyboy and the mysterious people carrying the middle initial “D,” all of whom smile at the thought of death, but none of that was known when the name of the island was originally revealed. There was literally not enough known context to translate the word into English correctly at the time!

There was also an ancient giant villain in one storyline whose translated name nobody could agree on; a consensus wasn’t reached until his descendant was introduced in the modern day, and his name explicitly written out in English by Oda (it’s “Oars”). To this day a debate still rages about whether the electric-powered tyrant/wannabe-god villain’s name is Enel or Ener or Eneru, despite the officially licensed English translation choosing “Eneru.”

The problem there is that Viz’s official licensed English translation has a history of not always getting it right themselves. A race of giants come from an island called “Elbaf,” or “Fable” backwards; Viz spelled it “Elbaph,” completely missing the reference. They changed the name of the Royal Family of Alabasta — a desert country inspired by Egypt — from “Nefertari” to “Nefeltari,” despite it being an obvious reference to the Egyptian Queen Nefertari. Early in the series Luffy and his crew land on the island that was the birthplace of the previous Pirate King, Gold Roger — and also the place where he was publicly executed. The original Japanese manga explicitly spelled out the island’s name out in English as “Loguetown,” but many fans thought that Oda got the L and the R mixed up again (as I mentioned, they’re interchangeable in Japanese) and insisted that it was called “Roguetown” because it had become a massive pirate gathering place. Apparently Viz agreed because they not only translated it as “Roguetown,” but even went as far as to edit the “L” into an “R” in the manga’s English spelling of the word. The problem is that both those fans and Viz were wrong. “Loguetown” was a reference to prologues and epilogues — it was the town where Gold Roger was born and died, “the town of beginning and ends.” You can’t always trust the official translations; even though they speak the language, they sometimes miss the nuance.

Translation isn’t just about translating the words either; it’s also about translating the tone. In Japanese One Piece has some mild swearing; it’s no Tarantino movie, but there’s a fair amount of mild curses. Luffy is constantly proclaiming that he’s going to kick a villain’s ass; Viz’s English translation has him declare that he’ll “clobber them!” Early on Sanji refers to everything as “shitty,” which Viz obviously translated as “crap.” Sometimes this worked well — such as translating “the shitty restaurant” to “Restaurant Le Crap” — but most of the time felt awkward because they would always use the word “crap” but never “crappy.” So if in Japanese Sanji would essentially say “you’re a shitty chef!” in English he would say “You crap-chef,” and that’s just awkward. English isn’t really spoken that way, which makes it a bad translation far moreso than the actual softening of the word.

(I’ll note that I don’t need One Piece to be full of swearing, but there are definitely moments where the milder word choices don’t match the intensity of a scene.)

There’s another word, “baka,” which is commonly translated to “stupid” or “idiot.” It’s a common insult in One Piece, but Viz often translates it to “fool,” which changes the tone entirely. Stupid or idiot sound playful, which is usually how it’s meant. “Fool” makes the speaker sound like a melodramatic supervillain, which works coming from a melodramatic supervillain but not from one of Luffy’s crew. Small touches like that leave a much bigger impact than you might imagine.

The first dozen or so volumes of the Viz’s translation also really commit to the pirate aesthetic. Yes, One Piece is a series about pirates, but while there’s the skull-and-crossbones and an occasional treasure chest and even one confirmed case of scurvy, its world is more defined by real world history, pop culture, and loud, colorful, boisterous, often downright campy ideas, aesthetics, and superpowers. It’s not Pirates of the Caribbean, and it’s not trying to be. The English translators of those early volumes, though, threw in pirate terms and speak whenever they could. Thankfully it was rarely in the mouths of one of Luffy’s crew, but quite often random villains or side-characters would call someone a “bilge-rat” or a “scurvy dog” or talk about “scuppering” a ship. When Sanji is told not to smoke, it’s because it will “scuttle” his taste. Again, it’s an awkward tone that isn’t present in any other translation and doesn’t really fit the world Oda is building. These aren’t those kind of pirates. I’m glad they eventually dropped it.

Viz also faced a legal hurdle. Luffy’s first mate is a swordsman named Roronoa Zoro, but because of the character Zorro, they were forced to change his name to Zolo in the Viz translation (though for some reason this doesn’t affect the current English Funimation dub of the anime). While it wasn’t Viz’s decision, that tiny alteration of one letter changes the feel of the entire name from something fierce to something a little more silly (Zolo sounds like a candy).

I think that’s my whole point here, honestly; tiny little changes in tone and context can have major repercussions on the reading experience. I enjoyed One Piece for years before Viz’s official release so I honestly don’t even notice Zolo — I still hear “Zoro” in my head when I read it — but first-time readers are missing a lot of nuances I only got because I survived years of fansubs, scantilations, and message board arguments over proper translation. Don’t get me wrong; 95% of the time the Viz translations are great, and I appreciate having official American One Piece manga I can own and flip through without the Russian Roulette of trying to find a reliable scantilation source. But as I read through them, I can’t help but to find little spots where I want to tinker with the wording or spelling because I know they don’t have the meaning exactly right, and that’s a bit of a bummer. Ultimately, it just reinforces the idea that, as important as translation is, you can never get the full 100% understanding of something if you don’t speak its original language. There’s always something lost, or missed, or downright botched.

The change of “Zoro” to “Zolo” also brings up the idea of censorship, which is something One Piece — especially its animated incarnation — has faced much of in America. But this is already too long of a newsletter as it is. I’ll bring you that in Part 2 on Thursday.

ABOUT

“Do You Know What I Love the Most?” is a newsletter from Spencer Irwin. Spencer is an enthusiast and writer from Newark, Delaware, who likes punk rock, comic books, working out, breakfast, and most of all, stories. His previous work appeared on Retcon Punch, One Week One Band, and Crisis on Infinite Chords, and he can be found on Twitter at @ThatSpenceGuy. If you like this newsletter, please subscribe and share with your friends!